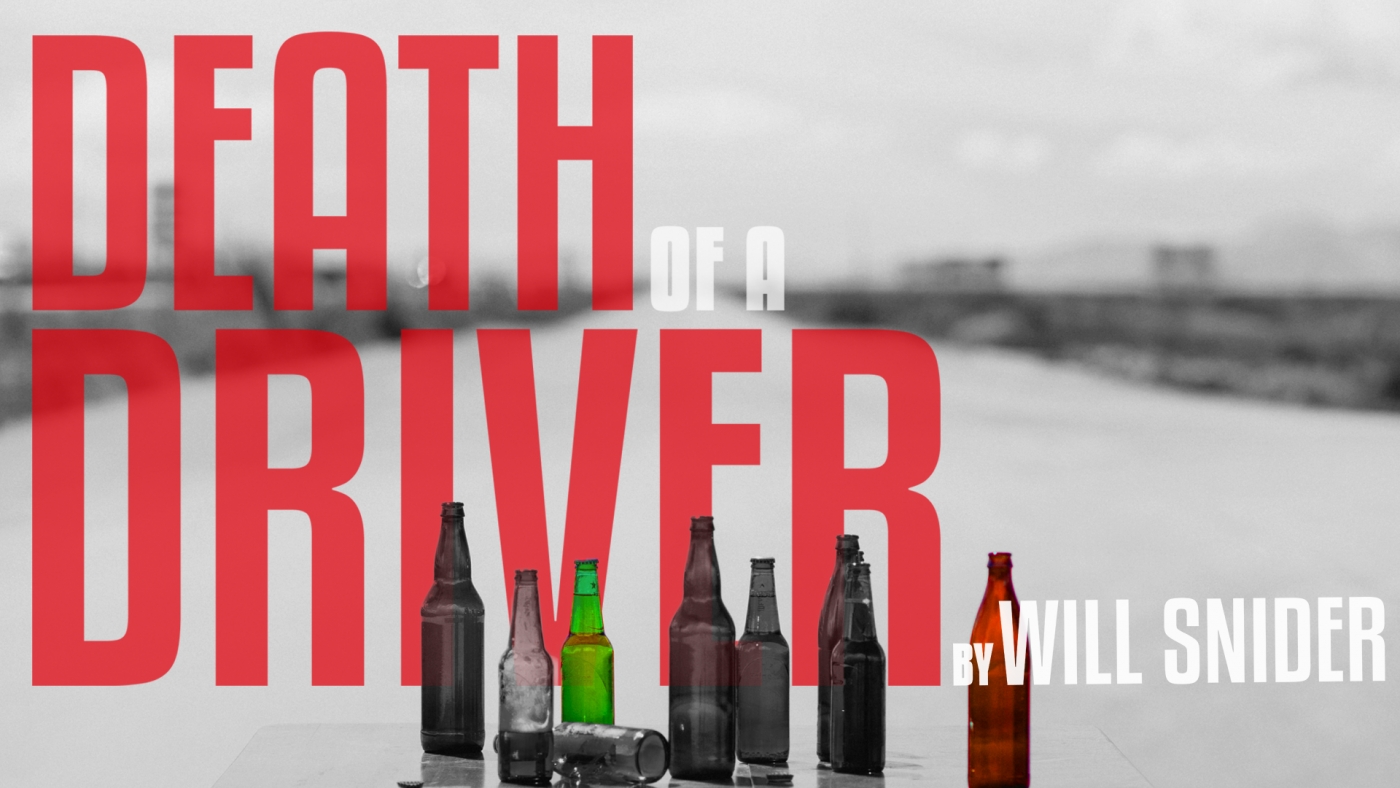

Note: The following remarks by DEATH OF A DRIVER Playwright Will Snider originally appeared in the production's playbill under the title "In the Room with Will Snider"

Salt Lake Acting Company and DEATH OF A DRIVER

By 2017, DEATH OF A DRIVER was dead. I wrote the first draft three years earlier and sent it to theaters hoping it would get a production. It didn’t. So I moved on. I wrote other things and filed this one away. Every six months I would reread the script and find myself missing the story of Kennedy and Sarah, wanting to see it on stage, but I didn’t think it would happen.

Then, just before Christmas 2017, I got an email from [former Associate Artistic Director] Shannon Musgrave inviting me to Utah. SLAC was hosting writers to work on plays without the pressure of a final presentation. They called it the Playwrights’ Lab. We were given a week in a room with a team of collaborators to do whatever we thought the play needed. I was lucky to have Patrick and Cassie, the two actors you will see tonight, and Andra, their director. We worked through the script scene-by-scene and staged it in several configurations. All the while I got feedback from Cynthia Fleming, David Kranes, and other Lab artists and made adjustments to the final scenes. By the end of the week, the play was back to life - it went on to have a world premiere starring Patrick in New York earlier this year. And now it’s come home to Utah, to the place responsible for its rebirth. Thank you to Cynthia and everyone else at SLAC for all you do for writers like me. Without the Lab, this play would never have been produced.

The Origins of the Play

“No one has a right to work in a place where their family doesn’t deal directly with the consequences of the work they do.”

I paraphrase words delivered by one of my college professors, Mahmood Mamdani, an anthropologist critical of foreign aid in his home country of Uganda. I listened to him, loved his writing and lectures, and immediately upon graduation violated his dictum. For three years I worked for an agricultural nonprofit in Kenya and Ethiopia that offered microloans of seed and fertilizer to small-scale farmers. We conducted rigorous harvest measurements to determine impact. We ran longitudinal household surveys to determine our effect on health and education.I believed then, and still do, that a good deal of development work is flawed and ineffective, but I felt our methods were different, we were different, I was different. Was I?

Alexandra Harbold, Kareem Fahmy, and Will Snider at the 2018 Playwrights' Lab

My language back then was the language of management consultants, of tech entrepreneurs, of MBA programs, and the use of this language resulted from, and reinforced, a reflexive anti-government stance, a feeling that solutions to socioeconomic problems were found far from polling stations, often in places that looked more like boardrooms. To me, electoral politics was a sideshow, a competition between elites, the result of which mattered little to the subsistence farmers I hoped to help. Anthropologist James Ferguson takes exception this. In his book The Anti-Politics Machine he criticizes development work for serving state needs above local needs, for being anti-political in the ways it ignores, and therefore supports, the political establishment. The more materially transformational foreign-led work is, the more it “helps,” the more it sustains the political status quo, which, in many places with significant foreign aid, is often ineffective if not outright oppressive. A bad government takes credit for good work.

Patrick J. Ssenjovu and Cassandra Stokes-Wylie rehearse during the 2018 Playwrights' Lab

But another part of me finds this argument too easy, a case for inertia, for ignoring pressing problems because they should be solved by local politics and therefore not solving them. Bad governments also have the ability to co-opt this anti-development discourse to defend their own legitimacy. And there is no way to close borders completely – the asymmetric exchange of resources, ideas, languages, and people cannot simply end, even if some wish it could. And so how do we go about transnational work ethically? Is there a way? DEATH OF A DRIVER is much more than the dramatization of my own cognitive dissonance around my early professional life, but I name it as one of the animating anxieties in the writing. It’s one way to watch the play – there are many others. This is the story of two people, of what we like to call the “personal,” and the way that this “personal” is transformed and constrained by national, cultural, economic, and gender difference. And I hope it’s not boring.

Thanks for coming.