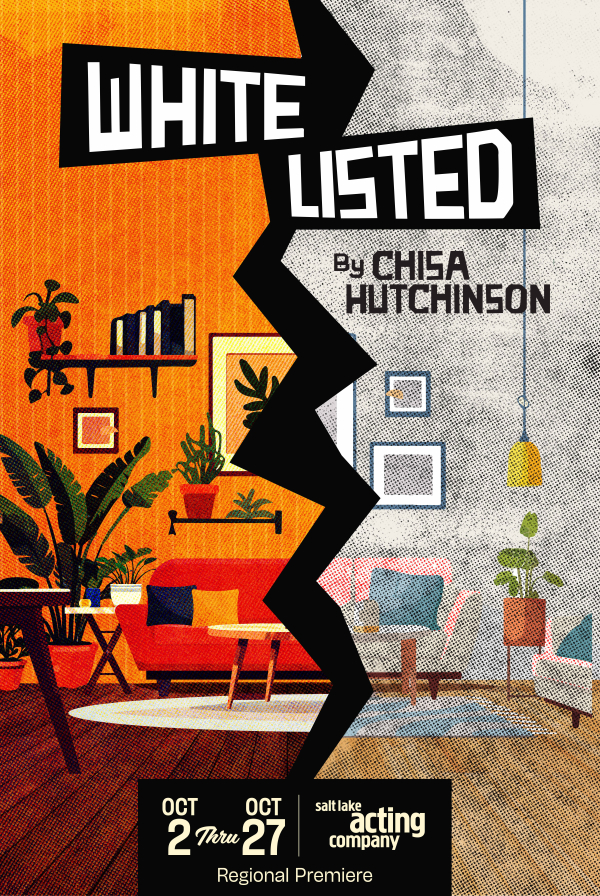

Salt Lake Acting Company’s season-opening production shatters stereotypes about black culture

By Barbara Bannon | Setpember 15, 2017

As I sat waiting for Salt Lake Acting Company’s production of “Surely Goodness and Mercy” to begin, I was struck by an irony. In the Upstairs Theatre, “Saturday’s Voyeur” was lambasting the lack of cultural and political diversity in Utah, while here in the Chapel Theatre, a play that celebrates difference and offers an insightful glimpse into another, unfamiliar way of life was about to open.

Playwright Chisa Hutchinson’s affectionate portrait of the unlikely alliance between a bright, abused teenager and a crotchety cafeteria worker is set in an urban middle school in Newark, N.J., and has an entirely African-American cast. Director Alicia Washington and Dee-Dee Darby-Duffin, who assisted her, are also African-American. It’s remarkable on every level that a place with the white-bread reputation of Utah is staging the play’s world premiere before it goes on to productions in Chicago and Newark as part of the National New Play Network.

“Surely Goodness and Mercy” is not a perfect play; its structure is cinematic, full of short choppy scenes that disrupt its continuity. But it’s so well-intentioned and has such a generous spirit, and its characters are so unpretentious and down-to-earth that it’s impossible not to like it. With the help of William Peterson’s constantly shifting lighting, Washington minimizes the breaks by avoiding blackouts and having characters move from one scene into the next. The Chapel’s intimate performing space and Thomas George’s eclectic, enfolding set also foster the flow.

Tino, an orphan who lives with his aunt, Alneesa, is smart, intensely curious and obsessed with the Bible, which he carries everywhere (the play’s title comes from Psalm 23). He attends a Baptist church he researches on Yelp, where the preacher emphasizes that “it is more blessed to give than to receive.” Volunteer your time, smile and “be a blessing,” he advises his congregation. When Tino notices that Bernadette, the cranky lunch lady at his school, seems sick and stiff, he recruits his friend Deja to join in devising a way to help her. “Nobody notices the nice things she does,” he tells Deja. “She’s the realest person I know.” Their actions precipitate a pay-it-forward reaction that benefits everyone.

The play’s dialogue and situations are so low-key and natural that the story simply unfolds before you. Yolanda Wood Strange flavors her portrait of the acerbic, no-nonsense Bernadette with flashes of a softer side, and Michelle Love-Day does her best to humanize the mean and bitter Alneesa, who is the weakest character in the play. We need to see what has made her the way she is to believe her cruelty.

The teenagers are double-cast and have limited performing experience. Darby-Duffin’s years as a schoolteacher helped them find their voices. On opening night, Clinton Bradt’s sweet-natured, talkative Tino and Jenna Newbold’s savvier, outspoken Deja were an appealing combination. Devin Losser and Kiara Riddle play the roles at other performances.

Jessica Greenberg’s sound design is especially effective. The organ music in the church scenes, children’s voices and school bells and funky music bring in the outside world to create a multilayered environment. Katie Rogel’s comfortable, everyday costumes deepen the sense of reality.